When I hear the oft-repeated phrase, “Microgrids are the future of energy,” I think, “Why the future? Why not now?”

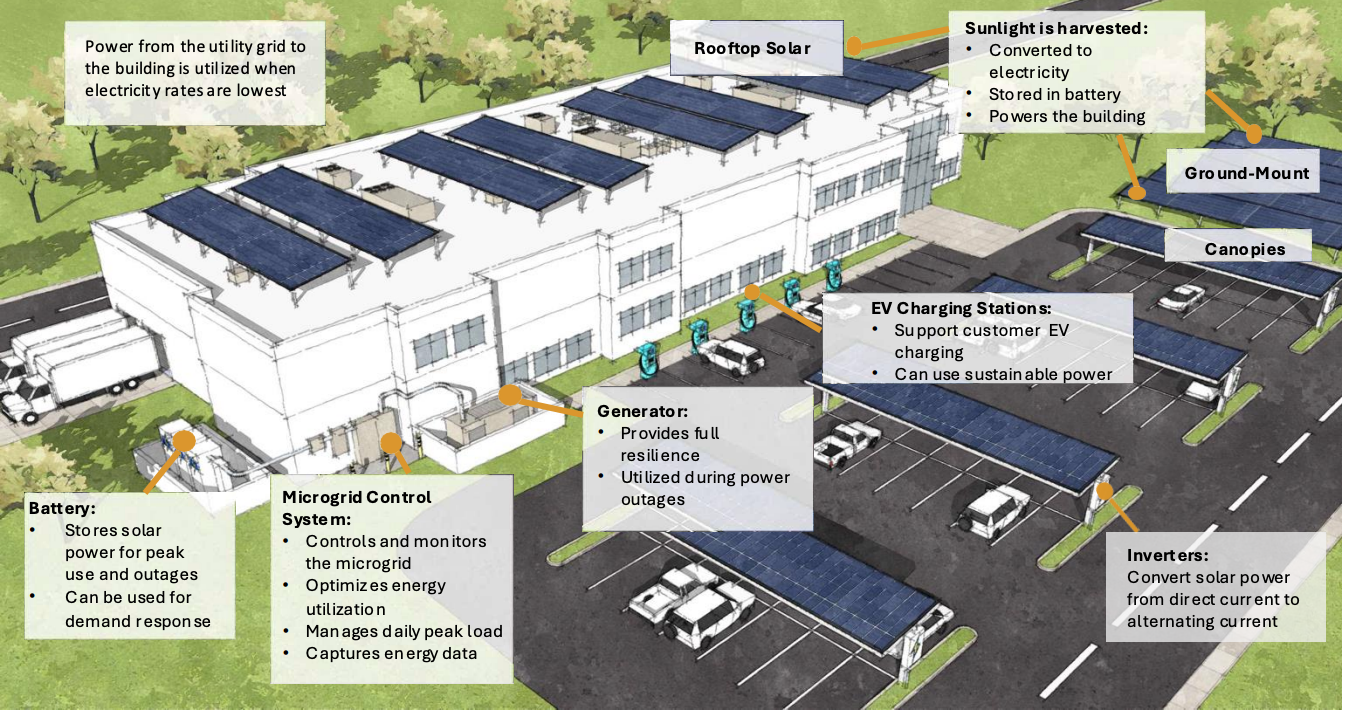

The technology has proven itself. Developers report strong demand. And you’ll find microgrids supplying energy for everything from grocery stores to data centers to military bases.

But microgrids remain a niche technology. On a 1,250 GW US grid, microgrids account for only about 9 GW, according to Wood Mackenzie.

What’s keeping them from scaling faster? Alok Singhania, a senior partner at Gridscape, has some interesting thoughts about the problem and how to fix it. I interviewed Singhania for a recent episode of the Energy Changemakers podcast.

It starts with how we think about them. Is a microgrid a project or product?

Today, many microgrids are handcrafted. A developer might work for years on one site, solving permitting puzzles, wrangling utility approvals, and integrating technologies that lack unifying standards. It’s expensive. It’s slow. And it’s hard to scale.

“Doing a custom development for a microgrid system every single time you go to a site — that’s expensive in our opinion, and also leads to quality issues,” Singhania said.

So what’s the alternative?

The rise of the modular microgrid

Gridscape is among the companies now focusing on creating various types of modular microgrids, where much of the system is built in a factory setting. These units are often delivered pre-engineered, tested, and ready for deployment. Most aren’t off-the-shelf in the traditional sense; some on-site engineering is still necessary. But they are standardized enough to skip months of tailoring and compress installation time.

It’s a strategy more common in consumer tech than utility planning, but it makes sense. The more predictable the product, the easier it is to finance, replicate and trust.

Gridscape manufactures a vertically integrated microgrid with battery systems, inverters, controllers, software, necessary electronics, and microgrid capability, he said.

Microgrids are the future, but fences are in the way

Of course, modularity isn’t for every site. Large facilities with complex energy needs still require detailed engineering.

And technology isn’t the only problem slowing the scale-up of microgrids. Tangled permitting and outdated utility rules and regulatory frameworks continue to hinder the industry.

We focused, for example, on the “over-the-fence” rule — a long-standing restriction that limits electricity sharing between properties with different owners.

If the over-the-fence rule didn’t exist, it would be possible to build several microgrids to serve a single electrical substation, relieving the system’s dependence on transmission lines.

“If a large percentage of substations are independent of the overall transmission system, think of the robustness, think of the cost savings that will come from that. Think of all the transmission lines you don’t have to upgrade,” Singhania said.

Wait, what’s a microgrid?

Then there’s education. Many local officials, inspectors, and regulators still don’t get what a microgrid is, let alone how to approve and regulate their development. Customers are curious but sometimes cautious because they think microgrids are new. They’re not.

All of these issues make it harder to scale microgrids. But at that same time forces are emerging that are driving new demand for microgrids. Singhania sees a lot of reason for optimism, even at a time when Washington appears to disfavor clean energy supports. Demand for energy is growing and it’s hard to quickly build utility-scale generation. Microgrids become the obvious alternative. That means a microgrid future might not be that far off.

Listen to our full discussion: How Can Microgrids Achieve the Holy Grail of Scalability? The Energy Changemakers Podcast is available on Apple, Spotify, YouTube, and other major podcast players.